Todd Shimoda, Oh!: A mystery of 'mono no aware'

Todd Shimoda, Oh!: A mystery of 'mono no aware'"Oh! is a hybrid novel, with nonfiction and artwork mixed in. The main storyline follows Zack Hara, a young Japanese American searching for an emotional life while traveling in Japan. Zack finds an ally in a professor and underground poet who introduces him to the concept of mono no aware, roughly translated as the emotive essence of things, or the sadness in beauty. The professor, grieving for a missing daughter, assigns Zack a set of mysterious tasks. Zack’s search for self-discovery turns into a search for the professor’s missing daughter, and draws him into the tragic phenomenon of suicide clubs."

“The mysterious tension between material things and emotional attachment to them oscillates throughout Japanese history and culture. With a keen and sympathetic eye, Todd Shimoda explores an individual's dangerous quest to waken his numb soul to this exquisite reverberation. As in Kawabata Yasunari's famous novella, The Master of Go, the lacrimae rerum of a dying tradition become a river, inexorably flowing toward the ocean of death. Fascinated, the reader cannot help but follow the flow.”—Liza Dalby

“Can an aesthetic concept developed in Japan 300 years ago be revived and made relevant to a contemporary American audience? This is what Todd Shimoda so masterly achieves in his fascinating novel Oh! A mystery of Mono no Aware. This is a journey through a delicate world of emotions and poetry on the part of a young Japanese American from Los Angeles who in his search for the native roots uncovers the complexities of being human in a world framed by skepticism and rationality. Structured as a thriller with a most unexpected finale, Shimoda’s novel unravels like a Japanese scroll—one cannot put it down until the last scene comes into full view and, with it, the realization that the realm of feelings (mono no aware) is far from being an innocent enterprise; it carries risks that one must be ready to pay in order to fully understand. This is a brilliant novel—it makes the reader feel the pleasure of thinking.”—Michael F. Marra

“This is the most compelling and complete account I have read of the exploration into the sudden, intense moment of awareness; the inherent state of sadness of life; the moments which, as Shimoda's character explains, makes us gasp 'oh!' with heightened awareness and wistfulness.”—Laura Pritchett

"On a lark, 20-something Zack Hara leaves his tepid life in L.A. for Japan. Following tiny shifts of fate, he quickly becomes fascinated by the ancient Japanese notion of mono no aware — an elusive concept that loosely means "the beauty of sad things," a sudden, intense moment of awareness that makes us cry "oh!"

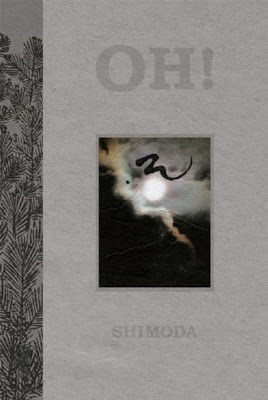

In search of his own moment of mono no aware, and intent on awakening his own emotional life, he becomes captivated by the suicide clubs that meet in the Aokigahara forest. In seamless counterpoint to the philosophical current, Shimoda shapes a delicate mystery that grows darker as the novel progresses. The book itself is a fine work of art, with a gorgeous, embossed cover, rice-paper-thin pages, and textured paper inserts with illustrations that offer clues to Zack's fate — a triumphant kick in the pants for anyone who doubts the future of paper-and-ink books." - Lucia Silva

"Detached and contemplative,"Oh!" draws the reader into a mesmerizing journey of discovery while also exploring contemporary Japanese pathologies along the way. This philosophical mystery gives us leads on understanding sadness, loss, family ties, identity and suicide. It is also a search for clues about what connects and motivates people, one that overlaps with the protagonist's own search for roots and attempts to break out of his shell

Zack Hara, an emotionally numb and alienated technical writer, suddenly decides to bolt Los Angeles and visit Japan, his ancestral home. Working illegally as an English conversation teacher in Numazu, Zack seems to exchange one rut for another. Zack, however, confides his empty emotional life to a local professor who prescribes tasks aimed at unlocking his sense of mono no aware (the pathos of things), an archaic term analyzed extensively throughout the text.

Indeed, the search for mono no aware and its meaning is an engaging leitmotif in "Oh!" For me, it embodies a sudden sense of wistful melancholy stirred by an intuition of impending loss, but here one discovers dozens of definitions and situations that evoke a sudden realization foreshadowed in the title. The text is framed by several stand-alone snippets of learned commentary on mono no aware that Shimoda presents as "exhibits," all referenced at the end of the book for the curious researcher.

In searching for mono no aware Zack quickly learns that it has little place in contemporary Japan. These days, his girlfriend says, "No one has time for mono no aware anymore." Most of the people we meet seem incurious and mindful of very little, merely going with the flow. Everyone except the underground poets he meets.

We follow Zack to the town where he thinks his grandfather is from and share his discovery that everything is not as it seems in the family tree. From there Zack turns his detective skills to suicides, visiting Aokigahara forest where many occur, and tracking down members of a suicide club. Ironically, in the midst of this obsessive investigation, one that focuses on emotional sensitivity and loneliness, he manages to lose his girlfriend, but doesn't seem able to connect the dots about his fear of intimacy. He also loses his job and has the police on his trail, but he perseveres.

Along the way Zack discovers that he and the professor have more in common than he thought; they both intellectualize emotions rather than feeling them. Finding the professor's missing child becomes Zack's new mission, but life and journeys are never straightforward. While searching for her in Tokyo he catches a suicide-club street performance near Harajuku and picks up a young girl who tells him, "The biggest problem of suicide is that it is boring. . . . It would be boring to kill yourself. It's all over. It would be much more interesting to stick around and see what happens." Amen.

Explaining the alternate logic of the suicide victim, Zack comments, "Death becomes the only answer to every question and situation. Death becomes the inescapable conclusion." As we expect, he joins an Internet suicide club, trying to understand and perhaps tap into the poignant emotions he lacks, that drive so many young people to despair. The members, however, don't want to talk about why they want to kill themselves, only about how to do it. He asks himself, "Is it better to feel nothing or feel their pain?" He finds the answer to his koan in a taped-up car in Aokigahara. It is this event that also inadvertently sparks the professor's own epiphany.

I must add that aside from Shimoda's tremendous story, sparingly etched, this is a beautiful book, one that feels handmade and produced with pride. Showing off the aesthetic possibilities in publishing, this weighty tome of poetry and palimpsest is lavishly illustrated and printed exquisitely with an embossed cover. Hats off to the book lovers at Chin Music Press!" - Jeff Kingston

"Recent articles claiming the demise of our ability to read long pieces of prose, digest an entire magazine article without feeling the urge to check some social networking website or another, or even use Google without ending up dumber, have left many wondering about the future of "books". That is far too large an issue to discuss here, but TODD SHIMODA's OH! A MYSTERY OF MONO NO AWARE seems to beg the question, albeit from a more positive starting point: his combination of story, illustration and highlighted footnotes either points towards a multimedia future for books -- or perhaps a look backwards to art that is all-encompassing and not focused on a single style.

Shimoda's third novel is a rich mystery: complex, entertaining, intelligent and an absolute pleasure to unravel and digest. Following the "Oh" is the mystery of mono no aware, which loosely translates in English as a type of "sensibility", a sense of sudden emotional awareness and the need to then express emotion.

Collaborating with his wife Linda for the illustrations, Shimoda tells the story of Zack Hara, who has gone to travel and live in Japan. Zack is drawn to his father's birthplace and in the course of illegally teaching English he meets Professor Imai, who tasks Zack to understand the concept of mono no aware. Zack also becomes interested in discovering more about the suicide clubs, whose members kill themselves in Aokigahara.

As in any good mystery, layers of apparently insignificant details reveal themselves to be critical; less typical is the addition of Zack's personal search for something completely intangible.

Certain design devices - short chapters, larger type and boxed footnotes centred in the middle of the page - seem to cater to our now reportedly shortened attention spans. But while Shimoda makes use of "strikethrough" and other typesetting effects, the poetry and lovely illustrations tend towards a completely different statement -- that a book can be so much more than a mere plot with beginning, middle and end.

At times, Oh! is reminiscent of a classic narrative, affixed with footnotes to help the reader along. But Shimoda's explanatory notes are given center stage, anchoring chapters as the plot moves forward: it is not often that the reader is privy to an author's reasoning for selecting a certain word, for crafting a particular reference.

In Oh! Shimoda's Professor Imai laments that modern Japanese no longer have an understanding of mono no aware, although the concept still remains central to the Japanese psyche. Early on, as Zack tries to confirm this statement, he is told: "No one has time for mono no aware anymore". Perhaps Shimoda (or Professor Imai) would be pleased to hear that upon asking two Japanese people about the expression, both were able to speak of it with relative ease.

An introspective read, with moments of humour and others of surprise, OH! A MYSTERY OF MONO NO AWARE unwinds slowly, as if Shimoda has tasked the reader towards the same journey of understanding mono no aware." - Melanie Ho

"My immediate impression of the book is an appreciation for its highly interdisciplinary aesthetic. The production values for Shimoda’s novel are first rate and it is very clear that much attention was paid to the visual experience of the narrative inasmuch as the written plot. I agree very much with

I won’t refer again to Shimoda’s career or the plotting of the novel as the previous reviewed has already completed an excellent summation of the main points. I do very much appreciate though the narrative pull that leads the readers onward. Zack Hara develops a really unique relationship with a professor while living in Japan, who provides Zack with a number of mini-adventures related to the exploration of “mono no aware,” the keen sense of loss that Zack does not seem to be able to relate to or understand. In this regard, the novel seems to be very much invested in the ways that Zack seeks to move out of an emotional stuntedness that is emblematized most carefully by his brief and desultory relationships with women. Shimoda sets the novel’s spatial trajectory vividly and we get a sense of the various cities and villages that Zack eventually travels to and explores. Each location becomes a terrain upon which the protagonist can investigate various philosophical musings. As the novel moves more firmly into its various mysteries, the pace picks up and we are left with a cliffhanger conclusion that is supposed to be unraveled through a careful consideration of the visuals that have been included. The images that do appear in tandem with the text often are incorporated in the space between the short chapters; in this regard, the reader is forced to look back and try to make sense of them in a different way. The “mystery” then unfolds in the artistic vision that Linda Shimoda provides. The very careful and organic union of art and fiction adds much to the texture and the success of this work. I am also reminded of the continuing transnational valences of Asian American fiction, having just reviewed Mary Yukari Waters’s The Favorites and having taught some fiction by the short story writer Shimon Tanaka. In this regard, Shimoda’s novel continues to flesh out the contemporary Japanese terrain from a Japanese American perspective. Zack is certainly interesting because as a Japanese American he possesses a complicated perspective of one who can sometimes “blend” in with others, but also finds himself strangely unmoored regardless of his relative linguistic proficiency. At various times, we see him either get mistaken for a “native” Japanese and at other times, as a Japanese American. This liminal space is key to enfiguring the complicated psychic terrain that Zack inhabits, one that is increasingly problematic to him as the novel moves forward.

I would highly recommend this book simply for its production value; Chin Music Press has made it a point to reconstruct the “novel” into a multifaceted experience. Of course, I think it would add much to any Asian American literature course or for any American literature course more generally; I think for myself I could see it easily as a match to the experimental impulses that we have seen, especially with the inclusion of art into literature. A course for instance could start with Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, move to a strong poetic sequence with Mong-lan and Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and conclude perhaps with Todd Shimoda’s Oh! The course could also incorporate graphic novels, such as Mine Okubo’s work, David Kirk Kim, Gene Luen Yang, Lynda Barry, and Shaun Tan. I think it would be really fun =)" - Stephen Hongsohn

Excerpt

"Seeking mono no aware in and with literary art: Colin Marshall talks to experimental novelist Todd Shimoda"

Interview with Wendy Nelson Tokunaga

Todd Shimoda, The Fourth Treasure, Vintage, 2003.

In The Fourth Treasure the stakes are even higher because the novel brings together two wildly different subjects—cutting edge neuroscience and Japanese calligraphy—while still telling an engaging and suspenseful, highly readable story.

In the case of this book, it is two people, husband and wife, who rise to these challenges: Todd, the writer, who has won awards and wide praise for his fiction, and is also a professor with a UC Berkeley Ph.D. in Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence (clearly, the brain is big enough); and Linda, the illustrator, an artist who has studied calligraphy in Japan (she's the fingers of the operation). Together, they have created a novel that is as full of complex characters and real suspense and romance as it is of beautiful artwork and multi-layered erudition."

"This isn’t the most moving novel I’ve read recently, but it’s in many ways the most interesting, and it’s certainly the most beautifully designed.

The author is a third-generation Japanese American who earned a Ph.D. at UC Berkeley and works at Colorado State University as a cognitive scientist doing research in artificial intelligence. This is his second novel.

The book’s title refers to the “four treasures” of shodô, the Japanese art of calligraphy: brush, paper, ink and inkstone. The novel is a romantic mystery of sorts built around an ancient inkstone in the possession of an elderly shodô teacher, or sensei, who owns a small studio in the East Bay. Bouncing back and forth from ancient and modern Kyoto to today’s Berkeley and San Francisco, it’s also the story of a young Japanese-American woman, Hana Suzuki, a student in neurobiology at Cal. When the sensei suffers a stroke, she decides to study how it affects his calligraphy—and through this search discovers much about herself.

The book makes splendid use of marginalia, including an ongoing series of explications of shodô, with gorgeous calligraphy by Shimoda’s wife Linda. Intellectually, it’s a fascinating exploration of this ancient art form, and also of the complexities of neuroscience. These qualities, and the breadth of Shimoda’s tale, make up for his blandness as a stylist. There’s a coolness in his prose that could be called Zen-like but sometimes just seems flat. I kept reading, though, captured by Shimoda’s intelligence and knowledge and the book’s physical beauty, if not by emotion." - Robert Speer

"A teacher of Japanese shodo (calligraphy) emerges from a stroke with both agraphia and aphasia, severely limiting his ability to communicate and rendering his kanji characters indecipherable. Meanwhile, across San Francisco, his former mistress, Hanako, waitresses at a Japanese restaurant and struggles to hide her MS from her daughter, Tina, a grad student in neuroscience and the love child of her affair with the calligrapher. Calligraphy serves as a meta-metaphor throughout this book, which, much like a calligraphic kanji symbol, is deliberately composed stroke by stroke. Skipping back and forth in time, from 17th-century Japan to modern northern California, Shimoda (365 Views of Mt. Fuji) traces the history of the potent Daizen Inkstone, from its discovery in a mountain stream to its hiding place in present-day Berkeley. Like a poem composed in kanji symbols, the story's overall meaning only emerges from the interplay between its characters, who are themselves invested with symbolic, conflicting qualities. They include the rebellious shodo sensei Zenzen and his traditionally minded student Gozen; Hanako and her thoroughly American daughter, Tina; two neuroscience professors, one a theorist, the other a pragmatist; and Tina's boyfriends, one a charismatic, charitable Latino doctor and the other a humorless Caucasian. When Tina takes the stroke-afflicted Zenzen as a subject for her studies, she is, quite literally, attempting to resolve the ancient mind-body conflict. Illustrations of the sensei's poststroke calligraphy and its Zen koan-like interpretations punctuate important points in the narrative. Reading this novel, which encompasses so many mysterious contrasts, is like an exercise in contemplating a beautiful piece of calligraphy; Shimoda has penned a skillful meditation on both art and life." - Publishers Weekly

"This is a love story that spans three decades and both sides of the Pacific as well as a mystery that revolves around a legendary ink stone and the lineage of a renowned school of Japanese calligraphy, or shodo. Shimano, a Japanese shodo teacher and master of the Daizen school, has an affair with Hanako, one of his pupils and the wife of a construction magnate who banishes her to America when he discovers her infidelity. Shimano follows Hanako to San Francisco, taking with him the ink stone that is the symbol of his school's prestige. In the present time of the novel, Shimano is a shodo teacher in Berkeley, while Hanako continues to live in San Francisco, their lives never intersecting. When Shimano has a stroke and loses the ability to speak and write, one of his students takes over the administration of his school and discovers the Daizen ink stone hidden among some old letters. Thus unfolds a chain of events that will bring Shimano and Hanako together one last time. A third-generation Japanese American and cognitive scientist, Shimoda keeps the plot elements in perfect balance, and the marginalia provide some interesting information about shodo that add depth to the narrative. Recommended for all collections." - Philip Santo

"Shimoda, a third-generation Japanese-American, again tells his story with calligraphic marginalia and reveals scientific aspects of the plot in parallel italic paragraphs about neuroscience. Although the marginalia of 365 Views, Shimoda's debut novel, baffled some, many found it useful and entertaining. The marginalia here enlightens us about the story, although this isn't clear until the plot finally smoothes out into a tight knit. Kiichi Shimano, an aging calligraphy teacher who has founded his own Zenzen school (and his own Zen calligraphic style) in San Francisco, comfortingly saddened by a lost love affair, suffers a stroke that takes away his power of speech and rational thought. But we have literally watched him teach calligraphy (Zen means Nothing-"Try not to think," he says), and he still wields a surreal power of communication in the eloquence of his unthinking brushwork. The fourth treasure of the title is the Daizen Inkstone passed down through the centuries to winners of calligraphy competitions. Shimano has taken it from Kyoto and kept it himself. Other parallels tell of Shimano's early years as a teacher in Kyoto while we follow the trials of Berkeley student and neuroscientist Tina Suzuki, who finds the gifted but stricken Shimano a golden subject for neuronal research in her Brain and Behavior Studies. Further parallel to the mystery of Shimano's neurons is the story of Tina's mother, a single parent with MS who keeps a scandalous past under wraps from her daughter. Is her secret tied to calligraphy and lost love? Is Shimano a more intimate ideal test subject than Tina knows? Is healing ki (lifeforce) a scientific reality-and better than marijuana for MS? Eternal quintessence in art and science." - Kirkus Reviews

"Writers tend to seek outsider status, which may explain why so many from the less micromanaged West, such as Booker finalist David Mitchell (Number9Dream) and Pico Iyer (The Global Soul), find in Japan a dependably sacrosanct home away from home. "In countries as hospitable as America," Iyer told the Voice, "I have one foot inside the community, one foot out. But in Japan, where I always have both feet out, I find solace." But what of the half-Japanese writer, the foreigner whose native-looking features might blur the lines between insider and outsider?

"My experiences in Japan were dichotomous," admits novelist Todd Shimoda during an interview in San Francisco, the principal setting for his new novel, The Fourth Treasure. "As a foreigner in Japan who spoke little Japanese, I was an outsider, of course. But as a Japanese American who at least looked the part, I could pass as an insider. If I didn't say too much."

Shimoda is a third-generation Japanese American, but his easygoing demeanor and faint twang betray his Southwestern childhood. The 47-year-old author and his wife and collaborator Linda, a visual artist, lived in Shizuoka prefecture from 1986 to 1987. Shimoda's Western rationalism (he had worked as an engineer) gave way to what he calls "something a little deeper. I climbed Mount Fuji with one of my Japanese students. He didn't speak much English. We could feel what one another was thinking, relating to each other on a Japanese level, in silence."

Shimoda's first book, 1998's 365 Views of Mt. Fuji, takes place in Japan. Fuji is the story of a disenchanted salaryman—an outsider from Japan's corporate cliques who gets drawn into a familial web of madness in pursuit of aesthetic fulfillment. Critics praised Fujifor its ambitious scope, its intertwined stories and impressionistic, ukiyo-e-inspired illustrations. But reading it can be as unsettling as a high-speed Internet surf: There's a surplus of pleasures, but you finish feeling kind of battered.

The Fourth Treasure is more satisfying. It traces the borders of insider/outsider status through an unlikely admixture of shodo (Japanese calligraphy) and science, combining stories of love (lost and found) and mystery with a bildungsroman, sounding a literary lament in a muted key.

The interrelated narratives coalesce around Hanako and Tina Suzuki: the former an immigrant who left Japan and her marriage after an illicit affair in the '70s, seeking solace and anonymity in a San Francisco tempura restaurant, and the latter her illegitimate daughter. The action shifts from California to Kobe and Kyoto with ease, pursuing the mystery of Tina's unknown father while recounting the fate of a missing shodo inkstone (the eponymous "fourth treasure"), a centuries-old talisman that enables its owner to transcend pain through art.

Yet personal identities remain as intangible as cultural boundaries—a challenge for the novelist and the reader. Tina is Shimoda's clearest protagonist, but she is a cipher even to herself. "Tina is confused, not only ethnically, but at a deeper level: who she is and who she can be," says Shimoda. She doesn't know who her father is. She doesn't know any Japanese and hasn't been to Japan, though she's sleeping with an archetypal American Japanophile, an ESL teacher named Mr. Robert, who is about as sexy as a Western tourist in samurai garb. She drifts through her graduate studies in neuroscience until a Berkeley-based shodo sensei, Mr. Robert's teacher, has a debilitating stroke, becoming the subject of Tina's research.

The Fourth Treasure is designed to meld Shimoda's Japanese heritage with his penchant for so-called "postmodern" conceits. Notes from a shodo instruction manual and a neuroscience textbook, together with poetic-sounding snippets from the recesses of the sensei's dreams, run down the margins in delicate typeface. Kanji, Japanese characters, appear in the margins courtesy of Linda. But the trained (or native) eye will quickly note distinctive idiosyncrasies in an art form known for its rigid formality. The kanji are frequently lopsided and expressionistic, and grow more so with the sensei's demented mind.

"The calligraphy in the novel was intended to be stylized," Shimoda says now, "to show the effects of the sensei's living in America, as well as the wracking emotions he brought with him. Many of the links between neuroscience and shodo, as shown through the sensei's stroke-induced brain damage, worked themselves into the story."

Shimoda wants to join disparate worlds: Japan and America, art and science, age and youth. He acknowledges Kobo Abe and Haruki Murakami as models, but he writes more like a careful, fact-juggling scientist with a searching imagination.

The author identifies most with a marginal figure in his novel, a private investigator named Kando, who follows Hanako from Japan to California at the behest of her crooked and powerful ex-husband. "His cool reaction to being confronted by thugs is one of resignation," explains Shimoda, "knowing that he crossed the insider-outsider line in Japan—and got caught." - Roland Kelts

"The novel is dead. Long live the novel! Last night, shortly after reading Todd Shimoda's unique and exuberant "The Fourth Treasure" and before beginning this review, I went out for a drink with some of my writing students. One young man, a survivor of the dot-com frenzy, said he'd heard the essence of that shimmering era summed up in a single remark: After hours of presentations by young dot-commers schmoozing with "old-style business," a suited veteran of industry pronounced his conclusion: "You're just a bunch of guys with ideas."

"Shimodaworks" is the name of the stunningly polished Web site where a browser can investigate and sample from past, current and forthcoming "projects" of author, consultant and engineering professor Shimoda and his artist-collaborator and wife, L.J.C. Shimoda. To term them a "couple of guys with ideas," though, would be to wildly understate the case. In addition to respective talents in the visual and storytelling arts, collectively the pair draws inspiration and connection from an array of fields that includes cybernetics, neurology, traditional Japanese scroll-painting, calligraphy and the Japanese language.

Each of these strands, bound together by the keen cross-cultural sensitivity of this nisei-generation American writer, plays a significant role in "The Fourth Treasure," a detective story that glides effortlessly between contemporary San Francisco and Kyoto, dips back into the mid-1970s and, with a fresh leap of imagination, returns to the classical Edo of the mid-17th century.

But the story itself is only the thickest strand of the novel as a whole, which is enriched by the artwork, which delivers a parallel unfolding of secrets. Calligraphy is real: in thick, black strokes and whorls on the page, far more than a metaphor. Calligraphy, or shodo, is the engine of this novel, the title of which derives from the four treasures, or necessities, of its practitioner: paper, ink, brush and inkstone.

The silent central figure of the tale, outwardly calm yet inwardly tormented, is an aging master calligrapher, a former star of that art in Japan. Self-exiled to Berkeley, he heads the obscure Zenzen (Nothing) School of Calligraphy. All he has brought with him from the illustrious academy in Kyoto is a stolen inkstone and an abraded heart.

"The Daizen Inkstone began its life as [a tiny part of] a mountain. At some point in its ancient history, the mountain began to disintegrate, as all objects do, as all people do. "Chipped in free fall, subsequently "smoothed and mellowed" by the force of a river, the stone is finally fished out by the wandering poet Jinmai: "'I think you would make an outstanding inkstone.' The stone, of course, had nothing to say." Nonetheless, tumbling down generations of calligrapher-poets, the accidental, perfect stone rose to being both a well of inspiration and a contested trophy.

Like other traditional art disciplines of Japan, shodo is ideally an all-consuming do, a discipline, a path for life. Ten thousand strokes for ten thousand days, the minimum prerequisite for mastery. Discipline, however, invites--in more sensitive individuals, it may even compel--transgression. Fittingly and hungrily, utterly nonjudgmental, "The Fourth Treasure" explores varieties of transgression in various contexts: adultery, dishonoring of parents, cheating on a lover, acceding to blackmail, acceding to bribery, handing out marijuana for medicinal cause and, not least, misappropriation of an MRI machine.

The front-stage protagonist of the story is Tina Suzuki, fatherless daughter of a self-denying immigrant-turned-restaurant waitress, Hanako Suzuki. Tina is a good girl, first-year Berkeley grad student in neuro. But after a long evening's work analyzing MRI results with a fellow grad student she fancies: "Tina smiled for a moment. 'I've been thinking of something kind of kinky. Have you ever wondered what your brain looks like when you're having an orgasm?'"

The fates of Tina, her self-sacrificing mother, the silent teacher and certain other players tie up as neatly as treasures bound in a furoshiki scarf. The confident reach of this text-plus-visual-aids is prodigious, exhilarating and provocative. If you read it, you may turn the last page and absorb the final hieroglyph only reluctantly.

Old-style novelists, move over? Maybe. But in this intriguing product of a new take on the Renaissance art workshop, a few traditional elements of fiction are much missed. The characters are sketchily drawn and without inward development. For all the dovetailing of a strong plot, the reader feels little emotional impact. And, ironically given the novel's subject and metaphor, there is little honor shown to the "ten thousand strokes" of the discipline of writing. The pervasive dispensing with the past perfect tense fosters confusion, and pronouns and modifying phrases are sometimes haphazardly assigned. Technical details? Perhaps. But in the case of language, essence dwells in style and syntax. A bold experiment, especially, needs the guidance of an old master." - Kai Maristed

"Few recent novels have caused me to think as much as TODD SHIMODA's THE FOURTH TREASURE. While undoubtedly intriguing, I haven't yet decided whether I think this is a "good book" or not. It's different, and there's not a lot to compare it against; I'm not even sure I know what "good" means in this context. I imagine I'll probably have to think about it for a while longer.

Author Shimoda, who is a professor of cognitive science as well as a writer, is skating on pretty thin ice here a lot of the time, and part of the thrill is wondering whether the ice'll crack and he'll fall in. The ice cracks in a few places, but he doesn't fall in.

We have come to accept that the substance of a work of literature -- the words -- is independent from its presentation, so that book -- the physical form -- is often used as a synonym for novel, i.e. the words, so much so that it now possible to source the "complete works" of a number of authors of the classics off the Internet: just the letters, no formatting. Paperbacks and hardcovers are identical except in heft.

TODD SHIMODA's THE FOURTH TREASURE takes us back to an earlier time, a much earlier time, when books were more than just words presented linearly, when the visual and even tactile context was crucial.

The Japanese (and Chinese) always knew this; the physical form of the words on paper, even the quality of the paper itself, was often as important as the words themselves.

THE FOURTH TREASURE communicates not just through the words on the page, but also through the beautiful and intriguing illustrations, both calligraphy and calligraphic imagery, that adorn the pages.

Perhaps it takes a cognitive scientist to remind us that the brain accepts information in many forms, and at many levels, simultaneously, and that information divorced from its context is much impoverished. Shimoda, as a scientist and writer, is clearly interested in the nature of consciousness and meaning. Tina, the neuroscience grad student protagonist, asks how mere synapses and neural pathways can give rise to meaning. The answer, which seems both scientific and traditionally Japanese at the same time, is that meaning is accumulated through use and context.

The four treasures alluded to in the title are the brush, the ink stick, the paper and the inkstone. The Daizen inkstone in the story -- a centuries-old inkstone --

has accumulated centuries of meaning. The inkstone itself, as a rock, has no meaning but for the accumulation of use, of being coveted, of being prized. And so it is with conscious experience; it is accumulated meaning.

Shimoda reminds us that books are also not just static objects, but that they acquire additional meaning through use (as anyone who makes use of a library will appreciate). Not prepared to wait for readers to add their own notes in the margin, or perhaps because that process would be too random, Shimoda has added his own marginalia, in the form of explanations of the origins and meaning of the calligraphy, scientific notes and comments from Tina's notebooks, as if the protagonist were annotating the book in which she is a character.

But, in addition to being an experiment in artistic fusion and a discourse on current developments in neuroscience, THE FOURTH TREASURE is also a novel about love and multicultural synthesis.

Tina is a first-year UC Berkeley grad student. Her mother Hanako, a Japanese immigrant, raised her alone by working as a waitress, and is now suffering from MS. Tina's somewhat odious japanophile boyfriend, Robert-san, is studying shodo, or calligraphy, from a Japanese sensei who suddenly has a stroke and suffers considerable brain damage as a result. The sensei's continued attempts at calligraphy yield what appears to be nonsense and simultaneously make him a valuable research subject for Tina's professors. The story stretches back into Japan, where Tina's mother and the sensei knew each other and back further to the origins of the inkstone. The story is populated with students and professors, a single mother, a gangster businessman, a private-eye and a piece of stone which is a much a character as any of them.

The story at times tiptoes on edge of the cliche without quite falling in -- there is a lot of bowing, oriental stoicism and manipulative gaijin ultimately bested by their more subtle Japanese opponents -- but for this and other reasons, the story provides tension, switching from the mundane to the sublime, from the problems of homework to those of art, from science to food, from Japan to California, from miso to coffee, from love to muscle spasms.

It is in many ways a haunting story, of love lost, of understanding gained. Some passages are beautiful, almost poetic, thrown in among the prose. And then there is actual poetry, short Japanese-style poems of a couple of lines, which illuminate the illustrations that illuminate the text.

I am completely out of depth when discussing Japanese art forms or poetry and so have no way of knowing whether the illustrator, L.J.C. Shimoda (the similarity in surname is no coincidence), has extended the traditional art of shodo calligraphy in ways that are considered proper.

But I'm not sure that I care. I had considered oriental calligraphy (as opposed to Western or Arabic calligraphy, which I had studied to at least some extent) to be a rather arcane art. I rather doubt I would ever actually read a book on shodo itself. By relating the art form to the story, and by insinuating explanations and examples into the annotations in the margins, THE FOURTH TREASURE succeeds in teaching a great deal and awakens, at least in me, a new interest and appreciation. Since author Shimoda does the same trick with several principles of neuroscience (something which I do know a little more about), and since he is a professor himself, one suspects a pedagogical purpose. It works, so who's complaining?

That being said, I have to wonder if either technique -- illuminations or marginalia -- will work if used more than rarely; part of the appeal is in its novelty; I don't know if it can be repeated too many times without becoming wearisome. There are good reasons why novels are almost never illustrated; the lack of visual images allows the reader to form his own. Perhaps books really are just words.

But THE FOURTH TREASURE sure is interesting, thought-provoking and well worth reading. And looking at. And maybe looking at again. I have little doubt that I'll pick the book up again in a few weeks to have another look at it." - Peter Gordon

Japan Times article

Asian Week Review

London Times review

Excerpt

Todd Shimoda: "Finding a Novel Aesthetic"

Todd Shimoda, 365 Views of Mt. Fuji: Algorithms of the Floating World

"Curator Keizo Yukawa flees a dead-end job in Tokyo to head a new museum devoted to 365 paintings of Mt. Fuji by the genius Takenoko, who died 100 years ago. Takenoko's legacy of madness infects each member of the Ono family, who own the Views but do not get along. Yukawa's manipulation by the Onos and his fascination with an algorithmically controlled daughter lead to many strange happenings and his ultimate disintegration. Symbolizing the fragmentation of mind in modern Japan, this novel uses threadlike character "bytes" and hundreds of Hokusai-inspired illustrations to suggest the nonlinear world below the high-tech veneer."

"As a lover of books, I sometimes curse the computer for what it has done to the written word, and occasionally to those who practice the art of novel writing most adeptly. In the name of interactivity, we can now read thinly plotted "cybernovels" on-line, or purchase CD-ROMs, mixing and matching narratives (sometimes a life's work) with a mouse click, artificially altering linear stories to suit our whims. We can participate in corporate-subsidized, hypertext serials, judged by much-praised, well-compensated novelists on holiday. Ah, progressŠ Todd Shimoda, who won the John Updike-judged Amazon.com serial competition last year, has structured his new novel by applying the mix-and-match, CD-ROM strategy to the page. Shimoda is a good writer-the main narrative piece of 365 Views of Mt. Fuji is a spare but engaging story, fraught with meditations on madness, sex, art, and spirituality. The problem here is in the constant flow of asides that fill the novel's margins-"character bytes," they're called-only occasionally supplying vital plot information or setting description, more often proving disjointed and distracting. Between the "bytes," the text, and the over 400 fine but cramped illustrations that fill nearly every page, the reader experiences a kind of constant sensory overload, detracting from the book's central focus-the story. Then again, maybe I've gotten it all wrong. Maybe the experience of shifting one's eyes from text to margin to picture is the real point of Shimoda's book, making it more of an exercise than a novel. While the sense of formal experiment is admirable, 365 Views of Mt. Fuji truly does belong in an on-line format, out on some Web site, where interactivity is a suitable substitute for pleasurable reading." - Independent Publisher

"The layout of the book is designed to agitate, if not actually madden, the reader. Yukawa's story is paralleled, in marginal notes, by those of the other characters, forcing eye and attention into a constant, dizzying zigzag. The whole complicated tale is a metaphor for the author's view of modern Japanese society as an assemblage of incompatible elements and traditions that create psychological civil war in its citizens. If the novel's purpose is grim, its action is lively and the symbolism is provocative." - Phoebe-Lou Adams

Virtual gallery of the book

Todd Shimoda's home page