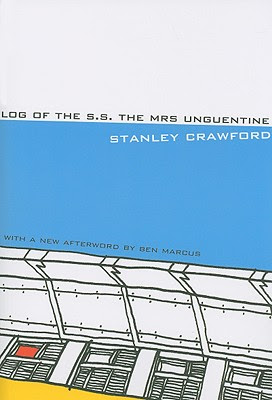

Stanley G. Crawford, Log of the S. S. the Mrs Unguentine, Dalkey Archive Press, 2008 (1972)

Stanley G. Crawford, Log of the S. S. the Mrs Unguentine, Dalkey Archive Press, 2008 (1972)"Forty years ago I first linked up with Unguentine and we made love on twin-hulled catamarans, sails a-billow, bless the seas . . ."

So begins the courtship of a certain Unguentine to the woman we know only as “Mrs. Unguentine,” the chronicler of their sad, fantastical tale. For forty years, they sail the seas together, alone on a giant land-covered barge of their own devising. They tend their gardens, raise a child, invent an artificial forest—all the while steering clear of civilization.

Log of the S.S. The Mrs Unguentine is a masterpiece of modern domestic life, a comic novel of closeness and difficulty, miscommunication and stubborn resolve. Rarely has a book so perfectly registered the secret solitude of marriage, how shared loneliness can result in a powerful bond."

"While Crawford's novel brings to mind the great literature of the sea (Moby-Dick, Mutiny on the Bounty, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner"), he doesn't allude to it; he doesn't have to. Log of the S.S. the Mrs. Unguentine - the book's most inelegant passage is its title - is a brave and audacious novel whose style, structure, story and language come together like strands of hemp spliced into an intricate knot." - L. A. Times

"1972 was a difficult year for the novel. This might—and perhaps should—be said of all years and times, since the novel is forever, genetically, finding everything a struggle and all things difficult (I think we're supposed to be worried when the novel does not do this). But 1972 was particularly special in its overshadowing, domineering, mattering way. It was a year that refused to cede an inch to the make-believe. The merely imaginary might finally have seemed trifling up against some of the defining and grisly moments of the century that collided that year and chewed up every available dose of attention in the culture. 1972, in short, produced the Watergate scandal, the Munich Massacre, and Bloody Sunday. Nixon traveled to China in 1972, and the last U.S. troops finally departed Vietnam. It wasn't clear that a novel had leverage against all of this atrocity, deceit, transgression, and milestone, let alone a novel posing as a ship’s log, narrated by a widowed ship slave who has witnessed logic-defying architecture, radical ecological invention, and faked a pregnancy while being banished—by her alcoholic, abusive husband—from all land and humanity.

Forget that painting (or sculpture, or the better poetry) was never asked to compete with the news, or to be the news. The novel’s weird burden of relevance—to reflect and anticipate the times, to grab headlines, to be somehow current, while not also disgracing the language—was being shirked all over the place, and Stanley Crawford, already unusually capable of uncoiling his brain and repacking it in his head in a new, gnarled design for every book he wrote, was chief among those writers who seemed siloed in a special, ahistorical field, working with private alchemical tools, producing work just out of tune enough to disrupt the flight of the birds that passed his hideout.

Architectural dreamwork, end-times seascapes so barren they seem cut from the pages of the Bible, coolly-rendered Rube Goldberg apparati, and the crushing sadness that results when you tie your emotional fortunes to a person whose tongue is so fat in his mouth he can barely speak, mark this little masterpiece of a novel. Cast as a soliloquy in the form of a ship’s log, a grief report from someone who has no good insurance she will ever be heard, the novel moves fluidly between its major forms: love song, a treatise on gardening at sea, an argument against the company of others, and a dark science expo for exquisite inventions like a hybrid lichen that makes things invisible. Published by Alfred A. Knopf under the editorial guidance of Gordon Lish, the fiction world’s singular Quixote—a champion of innovative styles and formal ambition—there may have been no better year in which to tuck such an odd, exquisite book. Instead of rushing for relevance and breaking the news, Crawford was taking the oldest news of all—it is strange and alone here, even when we are surrounded by people, and there is a great degree of pain to be felt—and reporting it as nautical confessional. The result, now thirty-six years later, seems to prove that interior news, the news of what it feels like to want too much from another person, will not readily smother under archival dust.

To be sure, Crawford’s focus in Log—the special toxins that steam off of a marriage—was happily at-large in the literary work of his peers (possibly so much at-large that its shadow is still staining the ground on which we walk), but while most of Crawford’s contemporaries were staging their loveless, white-knuckle relationship fiction in a spume of alcohol, boxed up in fresh suburban sheet rock, Crawford put his unhappily married couple, the Unguentines, to sea, rendered them as solitary (if not so innocent) as Adam and Eve, and he cursed them to be so awkwardly fit for human behavior that every kind of congress had to be reinvented and mythologized anew. If The Mrs Unguentine is so large and equipped it seems more like an island, it is also a floating stage for human experimentation, beyond the strictures of society, and the novel itself is a playbook for rethinking just what two people are supposed to do together when most of the livable world is out of reach. And to make their dilemma special, so we could see the nosedive of the Unguentines’ failed love through a crystal lens that Crawford ground himself from his own blend, he canopied the bad marriage with a fantastical dome, a literary invention so beautiful it doesn’t hog the spotlight so much as become a kind of distorted monocle through which to see this experiment in isolation, gardening, and love go terribly, terribly wrong. This may have been the first time that readers could sample a collision of such radically different literary sensibilities as Ingmar Bergman and Jules Verne: the bleak, life-loathing (affirming, loathing, affirming, who knows anymore) sensibility of the great artist of domestic cruelty, Bergman, with the wondrous vision and spectacle of Verne, the adventure story mad scientist. Call it Scenes from a Marriage on a Mysterious Island, because The Mrs Unguentine is more landmass than boat, a garden of Eden with very little joy and not one dose of shame, where the only solution to the endless pain of love is to hurl oneself overboard, which Mr. Unguentine does, only to keep courting his woman from the deeps, or from the dead, it isn’t really clear. Faking his own death just to reset the romance and return to courting? Colossally cruel or intensely romantic, or maybe both? This was the highest drama, a marriage on the rocks set in the weird colors of, if not science fiction, then really strange fiction that hews as much to ship design and greenhouse invention as it does to characters. The aloof approach to the sanctity of marriage, what indeed at times can seem like a satire of bad marriage fiction (she wants to talk, he wants to work and be alone, she wants kids, he drinks, he hits, she lies, he disappears), lulls us into susceptibility for the deep magic that occurs on this boat, and it would prove to be Stanley Crawford’s perfect art in later books to stage his deeply human stories—stories about the failure to love properly or deeply or at all—in bizarre, defended, solipsistic worlds.

Crawford’s description of the dome, secreted into the text with bored, offhand logic, introduces a theme that would later become a long-standing obsession (in such books as Some Instructions [1978] and Petroleum Man [2005]): patriarchs who cruelly show their love through radical inventions and the construction of ingenious, if useless, systems. If these men cannot much speak or love or hug, if they can’t be basically kind and open and interested, they can impart information, a syllabus wrenched from an arcane mind, with the hopes that it will be received as the ultimate loving gift. As much as we hear of Mr. Unguentine’s failure at human interaction, the entire ship’s design seems somehow his best act of love. Every bit of rigging and composting is a shrine. He will take his wife away to sea and never explain why, or even speak. He will fashion a secret identity for himself that brooks no interruption or interrogation. But in return he will build her a more fascinating world than any she could expect on land, even while depriving her of the basic things she wants. It’s a complicated way to show love, full of spectacle, vain performance, and ego. The irony is so entirely not lost on Mrs. Unguentine that she’s crushed by it.

In Crawford’s memoir of farming, A Garlic Testament (1992), he remarks of himself that, as a young man, he "developed a craving for what I called the real." It is his pursuit of this goal, in a body of work that is as rigorously inventive as it is obsessed with the human tragedy, that has marked him as a writer attuned to the most potent, and timeless, possibilities in literary fiction." - Ben Marcus

"This is one damn weird love story. This is one strange quest. This is one bizarre boat. These are a couple of strange characters we’ve got here. This book feels like a dare, as in I dare you not to believe this. What a boat! Mrs. Unguentine takes pretty much the whole book to describe it. They grow a garden on the thing. They grow a field, they grow a forest so high Unguentine can’t navigate from the pilot house, and they paddle around lost for years and years. The barge feels like your wildest dreams—think Seuss, Oz, Alice—and but this boat surpasses them in sadness and romance. A lost ark with five-hundred sails.

Yes, it seems that God has gone and drown the earth again, forgot his promise not to (He’s always been a disappointment that way), but more than the story of Noah, the book evokes Adam and Eve, man and woman in love and in conflict, locked together alone for forty years. At heart the book is about the loneliness of love, how even in the deepest love you can’t really know your mate. Yet it may be that very not-knowing that binds us to the beloved, keeps us longing to be closer, always on the verge of understanding, always on the verge of confusion.

And it’s no surprise that Gordon Lish loved the book. It contains all the Lishian prescriptions with regard to sound and swerve, like take the sentence, “And no wonder, for what was then called land, that shambles, was a sorry surface unfit for the conduct of anything but a harrowing traffic.” [p. 15] Notice the repetition of consonants and vowels:

wonder/what/was/harrow

and/land/that/sham/ har/traff

was/sorry/sur/face

un/duct

fit/duct/fic

And notice the swerves, the way “that shambles” upsets the preceding word “land,” for example. The weirdest part of it all for me is that I have actually met Mrs. Unguentine. I came across her in one of my more desperate, unfortunate equatorial wanderings. I thought I’d lost humanity altogether and then there she was. The barge had finally lodged into the sludge-swamp and stuck, stranding her there, half on land and half in sea. She came out to greet me. For a second, when I first saw her, I thought “Mrs. Howell!” and then when she called out to me, I thought “Nazi!” but then I knew who she was. So this was the sodden end of her sea journey. She had made the deck into a living room—stuffed chairs, doilies, all of it moldy and ruined in the tropical damp. Trunks full of faded gowns. But where was Unguentine? I wondered. I heard a clanging, from above or below. “My husband,” she said, and shrugged. Of course he was there, because that man, he could beat her, he could destroy what they both loved, he could keep silent for years, he could disappear from sight, jump into the sea, but one thing he could not do is desert her." - Deb Olin Unferth

"Just over one hundred pages long, Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine is a document that could, with a little effort, be ripped from its spine, stuffed inside a large bottle, and tossed end over end into the sea. The publishing history of Stanley Crawford’s sad, serene fiction resembles the fate of a message so transmitted, a hermetically sealed SOS riding out the decades. First issued by Knopf in 1972, the novel resurfaced sixteen years later thanks to Living Batch Press, with an aggressively drab cover resembling that of a Dover Thrift Edition. Now Dalkey has netted it from oblivion once more, and this re-rediscovery well suits the book’s elegant obsession with time and memory. As the titular character muses about her husband’s suicide, “it seems rather an almost gradual process... as if, through some gentle law of nature, his disappearance would be followed by his gradual reemergence, that he would come back, so on, so forth.”

Log weds form and function; it’s a book about a lachrymal life lived entirely at sea that uses the comma splice, the ragged right-hand margin, the pounding rhythms caught by Crawford’s unerring ear and eye, to set the reader at sea herself. Chapter 5 begins with a litany: “Unguentine, suicide, the business card, the barge, alcoholic’s leap into the sea, bottle, grey lips, boughs dragging in sea currents.” An explanation follows soon enough, but for the space of that single verbless sentence, we’re happily helpless, a wave of sensation breaking over us with each precisely captured item.

Plot has dissolved before the book even begins: Unguentine is dead, a man deliberately overboard, and now his widow will remember, fret, regret, and, like a figure out of Beckett, go on. The barge she and Unguentine created over decades—a would-be pleasure dome, full of wonders both natural and manmade, without the couple once setting foot on shore—is a metaphor for marriage, of course, and the singularly unhappy state of theirs washes nearly every page, whatever its wonders, with tears. Submerged thoughts are subject to decay, dramatically illustrated in a letter Mrs. U. never gives her husband, in which she attempts to explicate “this whole sequence of events which I now believe is leading us absolutely nowhere. owhere. where. here. ere. re. e.”

At one point, Unguentine “fastened down and hooked up the five hundred sails each the size of a manly handkerchief, each subtly controlled by the cable system from the pilot-house where he had installed a great lever, hand-carved and amazing, with which the sails might be trimmed at three speeds, Slow, Moderate, Fast.” Like all perfect books, everything is a metaphor for everything else: Unguentine’s genius for invention and ceaseless need to control are reflected in that sentence, as is Crawford’s subtly restrained prose style itself.

Readers familiar with Crawford’s Petroleum Man (2005), a die-hard materialist’s weltanschauung in one-sided epistolary form, or Some Instructions to My Wife Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage and to My Son and Daughter Concerning the Conduct of Their Childhood (1978), which is exactly what it says it is, will find in Mrs. Unguentine a crucial countervoice, who serves as antidote to the brutally (if hilariously) domineering men of those more recent books.

But even as Crawford re-creates the Unguentines’ sorry and often speechless union, he keeps his sense of the absurd, even cartoonish. “Unguentine drank; my fury went into tossing huge salads,” his wife recounts. Accidentally rupturing the hull with a board, she is “expecting to be enveloped in a shower of water or a jumbled whirlpool, be pursued or floated up the stairs and shot into the air as the whole barge crumbled into pieces and sank into the mud and water”—you can almost hear the Looney Tunes score.

Crawford turns things topsy-turvy at every opportunity, teasing out each absurdity and nuance of their waterborne circumstances. Unguentine has “terrestrial asthma,” getting land sick the way others get seasick; one night, the sky is “dimmed by the golden dusts of some far desert, a land in the air.”

The barge simultaneously suggests the Garden of Eden and Noah’s ark. In a prelude to the central heartbreak of the book, the couple mate, in a scene of deeply comic weirdness. Unguentine emerges “naked from the trees, his organ full and erect and painted purple,” and the critters gather as the pair get it on: “Our dogs, sensing an event taking place, came and sat respectfully at a distance at the edge of the lawn, bright eyes with flicking, hairy lids and limp, swinging tongues, panting. Soon they were joined by the cat and the goat, also some of the chickens, one of the ducks.”

For all its surface unreality and seeming lack of story, Log is tremendously moving. Though not quite a page-turner—there’s a density to the prose that prevents reading too many chapters at a stretch—Crawford tenaciously maintains focus on the marriage long since undone. (Indeed, it was doomed from the first, a wedding held in absentia: “We were married by telephone when the great cable was laid across the ocean floor well before the weather turned so foul,” Mrs. Unguentine relates on the first page.) Just as Unguentine powers the barge with his five hundred handkerchief-size sails, Crawford shovels his many metaphors into the book’s emotional engine.

Like that second the in its title, Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine is a stubborn creation that demands attention, and that odd surname is right on the money: This formally seamless book stings and soothes, like the most potent ointment, applied to literature too content to play it far too safe." - Ed Park

"ORIGINALLY published in 1972, Stanley Crawford's allegorical novel "Log of the S.S. the Mrs. Unguentine" has been in and out of print for years. Newly reissued after much time adrift, the book is long overdue for a heroic homecoming.

The novel is written in the form of a ship's log, albeit one bereft of dates, times or coordinates. Rather than hard facts, we are presented with the 40-year history of the Unguentine marriage as the couple roams the seven seas aboard a garbage barge. At the start, Mrs. Unguentine reveals that her alcoholic husband has committed suicide by taking a one-way trip to Davy Jones' locker with a "bottle clutched to his lips."

Information is presented in short, terse paragraphs that become increasingly expansive as Mrs. Unguentine mulls over her marriage. There's not much to say at first. Then a few complaints. (She wants a baby. He drinks too much.) Ultimately, the narrative blossoms into long, urgent paragraphs that stretch for pages. Imagine Donald Barthelme sending messages in a bottle to Gertrude Stein. "The seas, the seas," she laments, "how I hated them then, and all their waters which glided us from chicanery to chicanery and in our wake, our youth, oil smears iridescent of all that might have been; but never was, never will be."

The plot is straightforward, but it's not always clear what's happening or, for that matter, where in the timeline things take place. It's not a matter of whether Mrs. Unguentine's narration is unreliable, but to what degree.

First, there's the matter of the barge, which, under her husband's maniacally capable direction, becomes a veritable Garden of Eden replete with "forty trees with an inner circle of evergreens, cool, dark, unchanging, and surrounded by a flowing ring of deciduous trees." In addition to this floating forest, there are vegetable gardens, a menagerie and a "strange body of water which swelled and shrank in size according to some principle I never grasped." With Herculean determination, Unguentine wills this wonderland into being and disappears into it. Each of the 40 trees is given a woman's name, and he spends his days concealed in the privacy of their boughs.

When he tires of the garden, Unguentine covers it with an enormous dome fashioned of high-impact glass, turning their island of plenty into a "silent, dark, aquarium." Ever restless, he uproots the trees and replaces them with replicas made of iron and cement. There's even a mechanism by which the leaves, meticulously hand-painted by his wife, can be released. Crawford carefully details their construction, but Mrs. Unguentine needs but one word to describe them: "monstrosities."

Clearly, "Log of the S.S. the Mrs. Unguentine" is a metaphor for marriage, but Crawford's work is more than a narrative Noah's ark. Like the barge, it's so rigorously constructed that we cannot help but suspend our disbelief. "Warm mornings," Mrs. Unguentine tells us, "we would take breakfast to the very end of the stern deck behind the pilot-house, sometimes sit on the deck itself, legs dangling overboard, as sea gulls threaded back and forth over our white wake and eyed our movements, our toast, fried eggs."

While Crawford's novel brings to mind the great literature of the sea ("Moby-Dick," "Mutiny on the Bounty" "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner"), he doesn't allude to it; he doesn't have to. "Log of the S.S. the Mrs. Unguentine" - the book's most inelegant passage is its title -- is a brave and audacious novel whose style, structure, story and language come together like strands of hemp spliced into an intricate knot.

Is the premise fantastic? Absolutely. But the novel's emotional truth is as instructive as any fable. Marriage, Crawford seems to be saying, is more than a long sea voyage: It's like being press-ganged onto a sloop ruled by a bullying first mate and a treacherous captain.

These aren't uncharted waters, but Crawford's approach is unique. His novel is to marriage what Cormac McCarthy's "The Road" is to parenting. In a world so audaciously cruel, our humanity depends on that which binds us to others. Whatever you want to call this essence, it's universally expressed through the institution of marriage -- the most complicated and confounding metaphor of all." - Jim Ruland

"Regarding Stanley G. Crawford’s Log of the S.S. Mrs. Unguentine, one could begin by saying it’s an incredibly bizarre tale of two mariners adrift for decades on a sea barge documented in log entries begun after one of the mariners sees the other commit suicide. One could marvel at how the characters travel on what amounts to a floating landfill from which they grow a dense forest, home to hundreds of birds, and how Unguentine, in a fit of inspired madness, destroys this Edenic garden and replaces it with an artificial one made with painted planks, pulleys, levers, and other assorted contraptions. One could comment on the mysterious, disturbing, oneiric, and sometimes surreal relationship between Unguentine and his wife, how they live without a word spoken between them for years. With the narrative’s numerous references to fertility, harvest, growth, and rebirth, a tidy parable can probably be teased out from it. You could also talk about how it’s set in a post-apocalyptic world and how it celebrates iconoclasm, individualism, etc. But none of this really gets at how this story comes together.

Rick Moody could have been describing Stanley G. Crawford when he wrote “It’s all about the sentences. It’s about the way the sentences move in the paragraphs. It’s about rhythm. It’s about the way emotion, in difficult circumstances, gets captured in language. It’s about instants of consciousness. It’s about besieged consciousness. It’s about love trouble. It’s about death. It’s about suicide. It’s about the body. It’s about skepticism. It’s against sentimentality. It’s against cheap sentiment. It’s about regret. It’s about survival. It’s about sentences used to enact and defend survival.” But whereas Amy Hempel relies on space, concision, brevity, Crawford’s effusive lyricism—his rolling, spiraling cadences, its alternating plaintive and plangent sentences—is really what this whole novel is about.

Have you ever “peeled” a baseball, removed its cowhide covering? I did once and found tightly-wound string wrapped around a cork and rubber sphere. Log of the S.S. Mrs. Unguentine is like that. There are strings and strings of words here. The language is so compact and dense that you wonder how it doesn’t unravel itself from the pressure, from its sheer intensity. Take for instance Mrs. Unguentine’s description of their vessel. It

was a barge, a barge such as is used to tow garbage out to sea with. It was the only way I would go out to sea again, I said. We got the thing for a song, garbage and all, rot, stink, and a flock of squabbling seagulls. We had the garbage covered with earth and planted trees and flowers, and there was a great canvas with brass fittings to cover it all up from the wind and the waves, and thus we set sail upon a course that kept us to temperate zones, for the sake of my plants. And many times we were halted by hostile navies who had never seen such a sight; once we were claimed by an impoverished government which sought an island cheap by virtue of confiscation. While I watered my plants, Unguentine drank. On some equator or other I added dogs and a cat who ate fish and provided fecal matter for my garden which came to flourish to such a degree that it grew impenetrable in places, while vine-reinforced leafy boughs overhung virtually the whole barge and we could go on for days on end without seeing each other, amused at our respective ends by visitations of uncanny birds.

Passages like these are set within even larger unbroken paragraphs and move like massive ice floes that slowly make its way somewhere across the earth’s surface. The log begins tentatively with several terse and almost stoic entries about their life, but they slowly develop into ravishing passages. At various points Mrs. Unguentine makes brief references to their destroyed world, a world of continual foul weather, brown fogs over cities, “land, that shambles, was a sorry surface unfit for the conduct of anything but a harrowing traffic.” But we’re given nothing more than that. Her thoughts are reserved strictly for their life on the barge, her husband’s many eccentricities, her thoughtful insights into the absurd dynamics of their relationship and communication. As the novel developed, I felt thoroughly inundated by the commanding waves of language, language full of desire, empathy, fascination, grief, and rapture. Even the simplest of things, like descriptions of daily routines, are suffused with lyricism. Mrs. Unguentine after marveling at the geodesic dome they had recently built on their barge relates how they “always rose early and ate just before sunrise in the mists like mildew on the surface of the sea, on colourless waters, on waters lightly tinted blue or pink, or sometimes yellow, calm waters flecked here and there with blue leaves and silver lips where a breeze would drive a ripple up. Several hundred yards out, that white line of foam which marked the border between fresh water and salt, for the vegetation of our barge generated so much fresh water that we were perpetually ringed by a sort of inner tube of it, a lake floating in the sea, over seventy feet deep, and where swam hundreds of carp-like descendants of goldfish that once lived in our fish-ponds, also minnows, guppies, angelfish, bluegills.” These are Melvillean cascades by way of Anne Michaels. But there’s also the list upon lists of Whitman, the rolling, rolling, rolling on the river of Twain, and the dark clouds forever on the horizon of Faulkner.

Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine demands total surrender. And there are so many gripping sentences that beg to be read aloud. Like these for instance, from the novel’s concluding paragraph where Mrs. Unguentine lays alone suffering from delusions on their deteriorating ship:

I submitted to fantasies of pregnancy, some comfort in my lethargy and waiting, of an elderly childbirth upon one of Unguentine’s old sperm which till now had lain dormant within my body like a grain entombed, to burst into germination long after all the old walls had fallen. And when the pains finally grew sharp I thought that death should come like that, like childbirth, into the birth of silence and no light—and I stood up one last time and pushed the curtains apart to have a glimpse across the gardens, my fence, to the waves upon waves of velvet green beyond. I fell then. Someone screamed, I heard sobs, I heard coughing; suddenly I wanted to sleep. But the light from the window was too bright. When I raised my head from the floor, my mouth agape and some strange noise lowly pouring from it, I looked across my huge stomach heaving with contractions and thought to see Unguentine flow slowly out from between my legs and crowd my knees, or a somewhat dwarfish version of him, yet with the white beard, the flowing white hair. He was crouching now, I saw his eyes blink open, I saw a smile flash across his damp face the instant before his features went rigid and he toppled over backwards with a heavy thud. I could no longer raise my head, see where he was; yet I knew now he had come back to me only to die, was dead, to smile only, no more. A rivulet of my blood was soon flowing across the floor in pursuit of him. Soon myself, my body. Thus I joined him." - John Madera

"Well, what a remarkable and unusual little book this is! First published in 1972, and clocking in at 107 pages long, The Log of the S.S. Mrs Ungunetine has been brought back to the world by Dalkey Archive Press, and I am very glad they decided to do so. Part contemplation of the solitude of marriage, part Jules Verne-style fantastic voyage in a fantastic vessel, it is an unlikely fusion of elements bound together with a sprinking of magic – but somehow, it all seems to work. The log of the title is being kept by Mrs Ungunetine – she and her husband are the sole inhabitants of a giant barge that over the years they have landscaped, cultivated and customised so that it’s virtually a floating island. They have a forest of trees, they grow fruit and vegetables, they have birds that landed by mistake and never left – in the hands of some writers, such an implausible creation (which the Ungunetines do manage to propel from place to place, initially by means of a dilapidated steam engine, and later by wind power alone) might function merely as a convenient location to isolate two characters, serving an almost metaphorical role. But Crawford devotes considerable imagination to the platform on which his characters reside, concocting all kinds of marvellous and implausible modifications, which being a fantasy geek I confess I wanted to read more about!

On the barge, the Unguentines’ relationship is peculiar in the extreme – it seems they communicate largely by way of notes, and their floating domain is clearly large enough that they can avoid one another with ease if they wish. Right at the beginning of the book, we discover that Mrs Unguentine is writing after the suicide of her husband, and she is looking back on their time together on the barge. The chronology is fragmentary, but seems to hint at a shared purpose in the beginning which fractured over many years, so that by the time she becomes a widow, the two are leading drastically separate lives. There is little sense of common purpose later on – one day, Unguentine decides he is going to cut down all the trees and replace them with synthetic alternatives, an act she cannot understand or support – and even the act of conceiving and rearing a child does not bring any unity, though it certainly brings its share of weirdness to proceedings.

The Log is an interesting exploration of communication and domestic partnership – the Unguentines, when they share some kind of mission, forge a unique life for themselves, but when their objectives diverge, they become ships that pass in the night. An alternative explanation is that their very shared purpose in creating their floating world consumed them and distracted them from the maintenance of their relationship. It’s an intriguing and enjoyable experience, if bittersweet, travelling with the Unguentines, and the fantastic creation that is their living barge will be dwellling in my imagination for some time to come." - Simon Appleby

"...The story of a trash barge covered in soil and planted like the Garden of Eden, with only Mr. and Mrs. Unguentine as its captain and crew, Mr. Crawford's book is a work of decisive imagination. Divided into 10 confessional chapters, the log, devoid of nautical measurements, is written by Mrs. Unguentine, who thinks that her husband has drowned.

It turns out that his apparent suicide was really an expedition in a diving bell. But after he comes back, we soon learn that he is never really present, emotionally. Over four or five decades afloat, he has gone years without speaking to Mrs. Unguentine, and so she suffers, referring with characteristic alliteration to "the silent stranger I now so selflessly serve."

But she is unreliable. As Ben Marcus notes in his Afterword, the marriage is not a loveless one; it is full of demonstration: The barge, which eventually boasts a high glinting dome, full of opening casements and rigged with quiet puffing sails, can be seen as an always-secret Valentine, prepared in silence, loaded with detail and sweet afterthoughts. But that vision, however sweet, is not what Mrs. Unguentine wants. She wants a child, and she wants land. In a reverie, she hears "all the roar and clatter of subways, the awful din of garbage cans being emptied: my own breathing, my heartbeats." While her husband madly putters, she carries a world of normalcy inside her.

Themes abound: Eden, apocalypse, the relationship of man to nature, the something-out-of-nothing gesture of a marriage. But in the experience of reading Mr. Crawford's short, dense book, these ideas are only tracings on the surface of his magnificent invention: the barge itself, a Rube Goldberg contraption that breaks down, ultimately, to a length of sentences. It is a creation not plastic but verbal. And Mrs. Unguentine speaks, it must be said, a beautiful but unbelievable speech. So much of American writing takes this tone of amazed writerly inspiration:

we both broke into song, into a lilting sort of aria, but unsyllabled and smooth and which trailed off into a low hum, charging the night sea until the horizon bubbled with sheet-lightning and the waters glowed with the pulsations of electronic plankton, and we fell silent.

The barge drifts, in the telling, made up as it goes along." - Beenjamin Lytal

Stanley G. Crawford, Some Instructions To My Wife, Dalkey Archive Press, 1985.

Stanley G. Crawford, Some Instructions To My Wife, Dalkey Archive Press, 1985."Swiftian satire from Crawford, whose novel takes the form of an instruction manual written for his family by a neo-Victorian horticulturist."

"Crawford's novel, which has the full title Some Instructions to My Wife Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage and to My Son and Daughter Concerning the Conduct of Their Childhood, is a wicked parody of the handbooks on being virtuous cranked out by countless Victorian writers. LJ's reviewer found the idea behind the book "a master stroke of comic inventiveness"

"From "Putting Things Away" to "The Marriage Almanac" (not to mention the pedantic "Index," in itself a comic wonder), Stanley Crawford gives the married, the unmarried, and the formerly married a classic satire on all the sanctimonious marriage manuals ever produced.

Starting with the complete title, Some Instructions to My Wife Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage, and to My Son and Daughter Concerning the Conduct of Their Childhood, a boorish narrator sets down some seventy-three pieces of advice to his wife, young son, and two-year-old daughter, intended to foster and maintain domestic tranquility in an age of anxiety. Taken literally, our neo-Victorian head of the house is a male chauvinist pig of sorts, but what reader would deny that the sources of Crawford's satire run deep in the American grain?

Some Instructions is the madly precise fantasy of a husband and father who has stepped through the marital looking glass just to see, from the other side, the perfectly kept house and the well-functioning marriage and family."

"Stanley Crawford's satire on Victorian marriage manuals cheerfully lampoons male domination fantasies that persist even in such enlightened times as these... Crawford negotiates the literary tightrope he has strung up faultlessly, providing a piercing and comical dissection of the modern institution of marriage." - Newsday

"Some Instructions might be seen as an extended paraphrase of that wonderful captionless Thurber cartoon of the house as predator; it might be called a searing indictment of the nuclear family in capitalist society; it might be described as a sustained performance of exceptional virtuosity." - Times Literary Supplement

"The title of Some Instructions... nicely conjures the Swiftian satire of its contents—the eccentric dictums of an autocratic husband attempting to keep the world's chaos at bay." - Publishers Weekly

"Reminiscent of instructions by Renaissance husbands to their younger wives is this witty manual of household management and deportment... no detail of household economy or personal deportment is too small to merit the squire's personal attention." - Booklist

"Some Instructions is hardly a novel at all—more a homiletic work of fiction, a code of family living reminiscent of Johathan Swift's Directions to Servants and Benjamin...more

Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanac. Its purported author is a literal-minded man with a taste for minutiae, the kind of character encountered again a decade later in Nicholson Baker's The Mezzanine." - New Yorker

"The disease of fatherhood, however retrograde and on the brink of extinction by classification, is, in the hands of Stanley Crawford, a necessary disorder, still painfully insightful and beautiful." - Ben Marcus

"Curt, artful and funny in a way that hushes laughter, Some Instructions is one of the most trenchant investigations yet into that favorite subject of American writers—the family." - Weekly Alibi

"Crawford's mini-sermons are so unmistakable that one cracks smiles if not stifles guffaws at this incredulous Man-ual on the Man-aging Influence which settles for nothing less than its own divine intervention." - Cups

"The charm of Crawford's book lies in the fact that while one scoffs at the 'instructor' and snickers at his semi-Victorian prose, there is an underpinning of contemporary American neurosis that makes it all ring true." - New Pages

Stanley G. Crawford, Gascoyne, Overlook, 2005. (1966)

Stanley G. Crawford, Gascoyne, Overlook, 2005. (1966)"In Stanley Crawford’s dynamically charged, hysterically black-comic first novel we meet Gascoyne, a man who spends whole weeks in his car, eating, sleeping and conducting his business via mobile phone. Gascoyne has found a new preoccupation – hunting down the killer of his business associate (last seen slithering away from the crime scene in a tree-sloth costume), and finding out how the southern California megalopolis has suddenly slipped out of his grasp. First published in 1966 Gascoyne is a hilarious look into a future that looks remarkably like the present."

Stanley G. Crawford, Petroleum Man, Overlook, 2006.

Stanley G. Crawford, Petroleum Man, Overlook, 2006."Petroleum Man is a novel of Swiftean malice and biting humor that challenges the dogmas of both sides of the current sociopolitical divide--blue states and red states, haves and havenots, trickle-down conservatives and bleeding-heart liberals. Bewildered by the odious "liberal democrat" tendencies of his son-in-law Chip, Leon Tuggs--self-made arch-capitalist billionaire, inventor of the ubiquitous and environmentally hazardous Thingie, and author of the influential General Theory of Industrial Sex--decides to rescue his grandchildren from a life of guilt, indecision, and existential anxiety by educating them in the way the world actually works and telling them the things no teacher or parent in our politically-correct and morally relative universe could ever venture to say. These life lessons to his grandchildren are accompanied by gifts--cast-iron replicas of the cars he has owned during his own life, a life in cars.

From the 1939 Ford Fordor Sedan, in which the idea for Tugg's first invention was conceived, to the 1992 Lincoln Town Car Stretch Limousine, the entree to a hysterically charged confrontation between Tuggs and his family, Petroleum Man takes delight in exposing the vanity and frailty of some of the most popularly held prejudices of our times."

"In the tradition of Gaddis's prepubescent entrepreneur and Elkin's aging franchiser, the billionaire narrator of Stanley Crawford's Petroleum Man is in thrall to the capitalist ideal of make the most, have the most--accumulation is happiness. Inventor of a ubiquitous product called simply The Thingie [c], this elderly tycoon is intent on sharing his hoard with no one other than his two grandchildren, Fabian and Rowena, upon whom he is also gradually bestowing models of every car, plane, or train he has ever owned. The slow creation of these model collections--one model at a time, on birthdays and special occasions--is the central narrative event of the novel, which is composed of a series of letters the old man writes the children on each occasion, letters he stores up to give them when they are older. Ostensibly about the history of his vehicles, the letters are in fact digressive encomiums to his own financial success, and are addressed as much to himself as to the children. In them, we are given bits of his "General Theory of Industrial Sex," long exhortations on the ignorance of the various "liberal democrats" that plague his existence (including his son-in-law, the children's father), and accounts of episodes with the grandchildren themselves, through which we see them grow over years into spoiled teens with no respect for their grandfather or his models. All this is both extremely funny and horrifyingly plausible. Like Mark Twain's better (darker) satires, Crawford's humor sits on the surface of every page, in the narrator's "conservative republican" opinions and in the clarity with which the absurdity of these opinions is laid bare. The narrator is not a buffoon; he understands perfectly well the social, political, and ecological havoc his success has brought the world, and is rather tickled by it. He is, by his own declaration, one of the Petroleum People--those elite few whose special purpose is "arranging our lives and the lives of others so as to use as much petroleum and derivative products and related natural resources as is humanly possible ... in order to replace the now clearly obsolete natural world with a model of vastly improved design." - Martin Riker

"It’s a truism that most great artists aren’t nice people, in exactly the same way that most great businessmen aren’t nice people, or in the same way that anyone who’s devoted to one thing above all will prove lacking in the rest of life. One starts thinking about this very quickly when considering the work of Stanley Crawford: because he does seem to be that rare example of the artist who seems to understand the problem of living decently. One reaches this conclusion from his non-fiction work, which focuses on agriculture; but one can also arrive there through his fiction. Almost all of it (Gascoyne, Log of the S. S. The Mrs. Unguentine, Some Instructions, this book) focuses sharply on dictatorial male characters who are set on ruining the world, domestically or more broadly construed, in some way. Travel Notes, his second novel, seems to diverge most widely from this plan, but the narrator of that book might be roped into this schema without too much trouble. Though satirical, Crawford’s monomaniacs might be seen as a critical inquiry: what makes people behave this way? And what can be done about them? Crawford’s own response is a life of rural agrarianism in New Mexico, but his continued treatment of these characters in his fiction suggests that he hasn’t finished trying to understand them as a problem.

Petroleum Man, as its title suggests, is his most explicitly political novel. Published in 2005, it can’t help but be read as a novel of the Bush administration. Leon Tuggs, the protagonists, deprecatingly refers to his adversaries with the specific epithet (a Reaganism?) “liberal democrats” (the italics are his); their opposite numbers are “Conservative Republications“. Tuggs is a close personal friend of the President; by his own account, he is the most wealthy businessman in America (and perhaps the world), having achieved this position by selling something named “the Thingie®” which is made out of wood, and the precise function of which is left unclear (a nod, perhaps, to what is made in Woollett in Henry James’s The Ambassadors); it is, he says, an “unchallenged tool used to keep track of the proliferating things of the world.” His “liberal democrat” son-in-law informs him that there is “a glob of Thingies® all stuck together the size of a small iceberg floating off the coast of Southern California and that Thingies® have cause the death of millions of ocean-going fish by getting stuck in their gills and seabirds by getting caught in their throats” (p. 86) – but Tuggs, every inch the industrial villain, has little time for such concerns. Tuggs writes the book while in the air in his private jets; with an eye to his legacy, he has embarked on a program to give his two grandchildren, Fabian and Rowena, a series of scale models of every car (with a few planes, for good measure) that he’s owned; each model comes with explanatory text telling, at least in part, his life story as well as detailing his ongoing struggles with the rest of his family and the broader world.

Despite having a family, Tuggs is much better with things than with people; his fortune, he explains, stems from his General Theory of Industrial Sex, which mostly goes unexplained, but seems to stem from his observation that since sex can be found everywhere in the metaphors of the industrial world (nuts and bolts, plugs and sockets, etc.) there is no need to look for it in the considerably messier world of people. The position of Tuggs is that of Ayn Rand: he sees a rational world in front of him (found though the lens of engineering), and is purposefully blind to everything outside of that world – his family in the throes of collapse around him. His grandchildren, to whom his narrative is ostensibly dedicated, don’t seem to be interested in the slightest in his educational program, being, as they are, scions of a wealthy family above all else. But telling his life story through cars owned is the only way Tuggs can express himself: his world is the world of things. He yearns for the day when human advance will finally overtake the natural world:

This should be not far off, according to the figures I am being supplied concerning the paving over of raw land and the converting of forests into useful industrial products like Thingies® and the plans for processing useless icebergs into drinking water and – of course – into bags of ice to help counter the effects of global warming, which I have always regarded as yet another business opportunity, perhaps the greatest ever in the history of civilization. At the present moment, the main tool is the computer – which appears to work flawlessly, however, only in the movies. (p. 130)

The discordant introduction of the computer here points out how oddly anachronistic Tuggs seems as a figure of the American businessman: while everything, of course, can be made from petroleum, his fixation on the thing (as opposed to the human) seems out of place in an American economy that’s increasingly virtualized. His hated son-in-law, a lawyer for an investment, might point the way forward: like most financiers, Chip (note the name, of course) produces nothing but the abstraction of more wealth. (Fabian and Rowena, the reader assumes, probably will never bother to actually have jobs; they trade away their collection of laboriously constructed metal models of their grandfather’s cars for cheap plastic copies and cash to make up for their lack of an allowance.) There’s something almost laudable in Tuggs’s function as a producer: he is monstrous, but in his ridiculousness he is a comprehensible figure: we can see how he arrived where he is. His position at the end of the book is predictable: though he is more wealthy than ever, his family refuses to speak to him, and his long-suffering wife is suing him for “being the source of a drift onto her organic fields of illegal pesticides or herbicides or other substances not approved for organic production” when thousands of miniature hamburgers dropped from helicopters fail to hit his birthday party, as intended.

It’s always surprising how few American novels are about the mechanisms of capitalism and its effect on the businessman: off the top of my head, there’s The Rise of Silas Lapham, Melville’s “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” Nathanael West’s A Cool Million, Gaddis’s J R, Richard Powers’s Gain. It’s a big subject: there should be more." - withhiddennoise.net

Stanley Crawford, The River in Winter: New and Selected Essays, University of New Mexico Press, 2004.

Stanley Crawford, The River in Winter: New and Selected Essays, University of New Mexico Press, 2004."A consequence of growing up in the rural Midwest is a sort of pragmatism when considering art. This isn’t a pragmatism that Peirce or James wouldn’t recognize; rather, it’s a need to know what something’s good for, if anything. There are two causes of this: first, an environment in which art doesn’t exist as a matter of course; and second, the Midwesterner’s deep-seated belief that they are normal. I left the Midwest a long time ago, but I still find this attitude in myself from time to time; I’m not very good at appreciating architecture, for example, in no small part because the buildings that I grew up with were functional and nothing more. It’s an attitude I find in my reaction to reading as well: wondering who would read anything comes naturally when you grow up in an environment where no one reads anything. Obviously, the Midwest is not a yardstick against which anything should be measured; but it’s hard to step outside yourself.

There’s thus something that I find reassuring in Stanley Crawford’s writing: a sense of balance between art and work. Crawford’s fiction doesn’t appear to have reached a very large readership, which is a shame, as he’s a fine writer: his novels are modest and have been spaced out across forty years, but each is distinct and inventive. In his non-fiction – Mayordomo and A Garlic Testament – a philosophy becomes more apparent. Crawford makes a living as a garlic farmer in New Mexico; it’s an occupation that he’s put as much thought into as his fiction. Crawford’s someone who’s thought a great deal about how he and his writing fit into the world: I find this easier to stomach than the Monsieur Teste-like figure that most contemporary writers cut. This isn’t the most reasoned response; it’s more instinctual than not, but it is there.

The River in Winter is not the sort of book of essays that one expects from a fiction writer: only one of the essays in this book, “The Village Novel,” has anything to do with fiction writing, and even there Crawford is oblique (his “village novel” is metaphorical rather than a book), pointing out that living successfully in a community (in his case, Dixon, New Mexico) largely precludes writing about it:

Writers who grow up hearing episodes and chapters of the village novel at the knees of parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles set out into the literary world with something far better than a formal education – but this is also the source of the grief they can suffer when they offer up the contents of the village novel as a real book, a novel. They will then be charged with betraying confidences and appropriating something that belongs to no one person, or for quite simply getting it all wrong. (p. 146)

Crawford’s concern in this book isn’t writing; rather, it’s about figuring out how to live. He adopts a “small is beautiful” stance, following E. F. Schumacher; he observes the natural world around him and the way that people live in it. A third of the book has to do with water, as did Mayordomo, his chronicle of his time spent running a community irrigation ditch; while that book was concerned with how one particular ditch was run, here his eye roves, considering the myriad forces at play controlling water rights (especially the longstanding water adjudication batter) in northern New Mexico:

The ultimate effect of the adjudication process is to allow land to be separated from water, with complex consequences at the local level... I have long argued that the fatal flaw of the adjudication process is that it allows the “commons value” of a water right to be privatized away and dissipated. Much of the commons value of water resides in the acequia system, which conveys the water from the river to the individual landowner. When that landowner is allowed to sell off his water right, he is also selling something which does not properly belong to him as an individual property owner, in the form of that portion of a commons which until then has underpinned and sustained the equity of his property as land and water. (pp. 69–70)

Crawford is talking about northern New Mexico’s idiosyncratic system of water distribution from his perspective as a small farmer; but he’s also aware that he’s suggesting the broader situation that all of us are in, a world increasingly full of reifications. While Crawford is too polite to make this a political book, his politics are apparent; as is a clear sense of morality. Comparisons might be drawn to Lewis Hyde; but Crawford seems to be more interested in people than in art. Later he considers the role of the funeral in his village and how we treat death in general:

Perhaps one of the reasons people leave villages all over the world is that they want to live in places where the lesson is not so relentlessly taught. Suburbs are places without graveyards, without necropolises. They zone out the dead. Like garbage and sewage, the dead are ferried away to special ghettos elsewhere – or anywhere. The modern liberal solution of scattering ashes to the wind seems to solve the problem nicely. By making the dead disappear in a puff of gray ash, we can conquer death itself. (p. 152)

It’s not all doom and gloom, of course; a number of these essays are attentive to the physical world. He considers the mud floor of his house and the apple crates that he’s reused for years in a manner not entirely dissimilar from Francis Ponge; but his is also an interest in human use and how we shape objects and the environment in which we live. His mud floor:

There are times when I have fretted over the unevenness of the floor, but in repairing it again last summer I realized that under our wear and tear it will continue to evolve in ways that other surfaces within the house will not, surfaces that will be recovered, smoothed down, painted over, again and again. The history inscribed in the surface of our mud floor is a version of the history of the house we built with our own hands and of our lives in it since 1971. (p. 9)

The reader will notice some repetitions in this book: the essays’s disparate original publications are doubtless to blame for this. This isn’t to say that the essays are repetitious: each stands alone complete, and might best be read that way rather than being gulped done all at once. This book feels like a coda to Mayordomo; while Crawford makes this seem entirely normal, the situation that he describes is so outside the experience of most Americans’ civil interactions that it stands redescription. It would be nice to have more from Crawford; but one senses that he’s busy living." - withhiddennoise.net

"Stanley Crawford is a writer whose work displays a deep understanding of the complex enterprise of being human. His first novel, the dark satire GASCOYNE, appeared in 1966. This eerily prophetic look at communication, consumption and consumerism could easily have been composed in the present day. Crawford’s second novel, Travel Notes (From Here To There) appeared in 1967. Log of The S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine was first published by Knopf in 1972. Unfortunately, the book fell out of print and for a time was revived by the University of New Mexico Press.

"Stanley Crawford is a writer whose work displays a deep understanding of the complex enterprise of being human. His first novel, the dark satire GASCOYNE, appeared in 1966. This eerily prophetic look at communication, consumption and consumerism could easily have been composed in the present day. Crawford’s second novel, Travel Notes (From Here To There) appeared in 1967. Log of The S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine was first published by Knopf in 1972. Unfortunately, the book fell out of print and for a time was revived by the University of New Mexico Press.Dalkey Archive has come to the rescue again; they also publish Crawford’s Some Instructions to My Wife. They have reprinted Crawford’s iconic novel, with a new afterword by Ben Marcus, so a new generation of readers can discover the unusual Unguentines and their namesake barge. Crawford has published one other novel, Petroleum Man in 2005 but has mostly focused on nonfiction, Mayordomo (1988), A Garlic Testament (1992) and A River in Winter (2003); all while operating the garlic farm that he and his wife RoseMary founded over 30 years ago in New Mexico.

Can you explain the genesis of Log of The S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine and the landscape of the novel upon its 1972 publication?

-I wrote my first novel on Lesbos, my second on Crete, and my third, Log, in San Francisco and Northern New Mexico in 1969-70. I had spent about seven years in Europe and South America during my 20s and early 30s, returning to the States in late '68. The transition was agonizing, and I stopped writing for about six months. Log came out of the blue in May of ‘69 -- a name in a short sentence. In retrospect, several themes went into it. The old couple on Killiney Hill near Dublin who lived in a greenhouse back of the main house, which they had carved up into three apartments, one of which my wife and I rented for six months before moving on to the States. RoseMary is Australian, daughter of a legendary mother whom I had not yet met. It's likely that they were the basic ingredients of the Unguentines.

I wrote the first draft of the novel in San Francisco and re-wrote it in Northern New Mexico in the spring of 1970. I remember receiving a tremendous boost in confidence in it when my English editor sent me a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude: I felt I was mining a small tributary or tendril of the vein Marquez had discovered. What else? I discovered Virginia Woolf about that time; also Edith Wharton. But I can't say what was generally happening in the literary world, in part because I had moved so far away from London and New York. At that time people were still wondering whether New Mexico was in the United States….

Unguentine's obsessiveness with their barge borders on the fanatic and his near muteness enhances this quality. Do you feel that his is a religious devotion and how is this aspect integral to the narrative?

- No; but all of my narrators are obsessives. I think his muteness was a way to represent and therefore deal with my own difficulties in returning to the States and trying to learn the new language of that rapidly changing and deeply polarized time. I felt I had come back to a foreign country and had to learn a new set of gestures and code words.

Communication and miscommunication are central themes in this novel. How does Mrs. Unguentine cope with the repeated rebuffs from her husband and how do her reactions impact their shared environment?

- Mrs. Unguentine weaves everything into her fluctuating narrative, the good, the bad, the flat. I think that's how she copes. Unguentine is fodder for her narrative fantasies. I can't say I knew it at the time except instinctively, but I think this is how many women cope, or coped, with their lot.

The marriage of the Unguentines is unorthodox at best and abusive at worst. However, within these poles there are moments of tenderness and joy. Is their relationship an extreme example of the shared solitude that develops in a long relationship?

- My wife's stepfather, a brilliant German chemist who had settled in Australia, died not long after RoseMary and I met on Crete. He was an erudite man, and several of his sayings worked their way into our relationship. One of them, to RoseMary's mother, his wife: "We are our predestined enemies." "Shared solitude" is a good way to put it.

Do you consider Unguentine an ecological novel?

-Written during what some considered apocalyptic times not unlike the present day, I imagine that Unguentine's decision to take to sea was a response to the then-state of the world. Yes, there are ecological elements. At the time of writing the novel I was fiercely interested in back-to-the land technologies and I certainly felt that urban living of the sort I had known most of my adult life was as we say now unsustainable. During that time Stuart Brand's Whole Earth Catalog was my bible. Other than that I had not done any reading in the still small ecological bookshelf. Certainly, Carson's Silent Spring was in the air, as was Francis Moore Lappe's Diet for a Small Planet. And certainly the neighboring hippie communes in Northern New Mexico -- none of which I knew directly -- probably had an influence. Except Lama, less a commune than an eclectic spiritual center, which I visited frequently in 1970.

You mentioned earlier that all of your narrators are obsessives. Why is this personality type such an appealing narrative vehicle for you? Do you consider yourself of a similar bent to some of your narrators?

- Either I'm a little more obsessive than most people, or else more aware of it, as are perhaps most artists. An obsession is a way to organize experience -- or distort it. Probably the writer who opened that door for me was Moliere, who used obsessions and their silly extremes to deflate pretensions of all sorts and even as political sallies to the extent that his times allowed him to do so.

In Ben Marcus's afterword he mentions that Gordon Lish took the book under his editorial aegis but I understand this is somewhat of a misconception.

- Lish was given a copy of the book by my editor, Robert Gottlieb, who was having trouble promoting it. Then at Esquire Magazine, Lish became a fan of the book, wrote me frequent notes, probably passed it on to Ann Beattie, who put it on her best books of the year list in, I think, The Village Voice.

You have used several structural devices in your novels, the diary in Petroleum Man, the domestic manual in Some Instructions to My Wife, as well as the ship's log in Mrs. Unguentine. What makes these frameworks so appropriate to your fiction?

- Two points. Sartre said something to the effect that history had stripped us of the right to assume the position of the god-like omniscient narrator hovering over the action as if he has nothing to do with it except tell the story. From this it follows that the narrator must be part of the story, which he can be telling to someone for stated or for ulterior motives, or both, or confiding to himself (or herself, in the case of Log) in order to make some sense of what has befallen herself or simply to leave a record of events. An audience, sometimes specific, sometimes shadowy or indefinite, is posited, someone other than "the reader" of conventional omniscient narration. That said, I must say that I can enjoy a well-constructed novel told by an omniscient narrator as well as anyone, and many great novels have been written this way. As a writer I may simply not have the confidence to assume such narrative certainty.

You and your wife have been running a garlic farm in New Mexico for over 30 years. You have written eloquently and passionately on the subject, i.e., A Garlic Testament. How did you become involved in this atypical agrarian venture?

- As a young writer I made a lot of money on my first novel, whose film rights were sold, though no movie has ever been made. I could have lived on in Europe another ten years, but when RoseMary and I met on Crete, got married, had our first child, things began to change. We came back to the States in late 1968, a time of urban violence and extreme political polarization over Vietnam. After six months in San Francisco, we followed new friends to Northern New Mexico, a la Easy Rider, took up gardening, then farming, built our own house, and all the rest. My years abroad had made me long for a life in which I had more control over the basic business of feeding ourselves and keeping warm in the winter, at a time when the political fabric of society was becoming shredded. During all this I was also discovering that I was not the sort of writer who could crank out a book every year, and that my gestation time was often slow and certainly unpredictable.

Why do you think Unguentine continues to garner such fervent devotion and dedicated acolytes some 36 years after its publication?

- Since I find it agonizing to re-read -- or re-live -- the novels, I'm never certain why people like them. Because they perhaps come from some deep place in the psyche? A couple of years ago, Mark Rudd of Weather Underground notoriety, confided to me that my first novel, GASCOYNE, was what radicalized him… As for Log, perhaps because it's a kind of luxuriant refuge from the world…?" - Interview with Sean P. Carroll

"Stanley Crawford, born in 1937, is the author of five novels (Gascoyne, Travel Notes, Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine, Some Instructions, and Petroleum Man) and three non-fiction works (Mayordomo, A Garlic Testament, and The River in Winter), and has been writing and farming with his wife Rose Mary in Dixon, New Mexico, for nearly forty years. His novel, Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine was reissued last September by the Dalkey Archive. A fantastical tale of a troubled husband and wife sailing the world on a raft of their own invention, its reissue has been praised by the Los Angeles Times as “a heroic homecoming...his novel is to marriage what Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is to parenting.”

Dalkey Archive’s reissue of The Log of the S.S. The Mrs. Unguentine, originally published in 1972, has garnered an impressive amount of critical attention. You have said that the novel was, in part, your response to the tumultuous atmosphere you found upon returning to the U.S. in 1969. Do you think that the current national mood, forty years later, has anything to do with the sudden revival of interest?

- Yes, but I hadn’t re-read the book for many years, perhaps decades, until Dalkey decided to reissue it last year. I came to think of it as an apocalyptic novel, which I suppose it is, but to a lesser degree than what I had come to imagine. It may be this, or the “freedom” from institutional and political constraints that the Unguentines seem to have attained that readers are picking up on, but reviewers have focused more on the relationship, the marriage, the interpersonal—or their pathological aspects. And the times are very different: 1968 and all that had to do with a younger generation trying to elbow its way into a society that was perceived as being repressive and controlling and murderous. Today, I think people are trying to find, or imagine, places of refuge during this slow-motion collapse. Perhaps the barge offers a sort of refuge.

Log is perhaps my favorite of your novels, yet its tone is quite different from the satirical humor of novels such as Gascoyne or Some Instructions that first attracted me to your work. When you wrote Log were you consciously working to write a different sort of novel, or was it more organic than that?

- No, it came out of the blue, after six months for the first time in my adult life of not writing at all, at the end of a time when I tried (again—there were several attempts at this) to paint. I remember quite clearly the somewhat gloomy room that served as my studio in our second floor apartment atop a Japanese restaurant, on the corner of Geary and 36th Avenue in San Francisco, the first lines emerging enigmatically from my Olivetti portable, which I left for a few days before continuing on with the story, in longer and longer sections, unbelieving at what was happening. Much later I could trace the filaments that wove themselves into the voice (to mix metaphors) and some of the imagery of the tale, but at the time it was thoroughly mysterious—and fearsomely delightful. Better, you might say, than “organic.”

In a recent interview with novelist Deb Olin Unfirth, you mentioned that ”Log would become a sort of imaginative blueprint to the next phase of our lives in Northern New Mexico as back-to-the-landers.” It’s interesting to think about such a fantastical novel serving as a “blueprint” for living—could you elaborate on how you see the relationship between the novel and your life in New Mexico?

- “Blueprint,” on reflection, is a little misleading. Yes, we built our house with our own hands, grew our own food, kept livestock, but what I discovered in Northern New Mexico (and had been long craving) was the social, was cooperation, collaboration, and dialogue about matters political. And of course history is still very much alive here, to perhaps an unusual degree in the States. Raising children was also at the core of all this. Unguentine sought to disentangle himself from the world, from the social and political and historical, and live in the mythical world of self-sufficiency; and if this was to a certain extent an illusion I was attracted to, our early years in New Mexico quickly disabused me of it. Of course the imagination is where one can safely try out such extremes.

It’s interesting to me that the cooperative and collective aspects of life in Northern New Mexico is a central theme in much of your nonfiction, whereas your fiction is often focused on individualists gone awry, and not, generally, on issues of place. Have you ever considered what accounts for this divergence of focus?

- Historically literature has celebrated the individual, and this was my training—not writing (I never took a writing course) but English and French literature. Why, in short, the novel is still considered dangerous in totalitarian and fundamentalist societies. As a rule the novel criticizes or even denigrates the collectivity from which, ironically, it emerges; by definition its protagonists are outsiders, misfits, criminals. Certainly there are novels that celebrate the collectivity. I think for example of Winifred Holtby’s wonderful West Riding. It’s been awhile since I’ve read it, but I was struck by its realistic portrayal of town meetings—the sort of thing Flaubert wonderfully satirized.

My actual training as a writer came through rubbing shoulders with experienced writers on Lesbos and Crete in the 1960s, William Golding among them. Eventually I came to see the destructive or stunting aspects of being an expatriate writer. I was good at languages, but in time I wondered whether this might be at the expense of keeping up with my own language and therefore writing. I also came to feel helpless, particularly after the Colonels’ Coup of April 21, 1967, turned Greece into a rightwing dictatorship that arrested a few Greek acquaintances (but quickly released them) and banned, among other things, the songs of Nikos Theodorakis. Politically helpless, helpless as a foreigner to take matters in common with others in hand.

It was this urge, most of all, that lured me back to the States. Fiction seems to me to be essentially a critical tool in an imaginative sense, and when I found myself settling down in Northern New Mexico, a place of strong characters and age-old traditions, I found myself without the writing tools to describe it. And wondered whether I should even presume to, as I was not much less of a foreigner among my Hispanic neighbors than I had been among the people of Lesbos or Crete or Paris. But in time, after seventeen years of mending fences, digging ditches, and planting my gardens, I tentatively wondered whether I might finally have earned the right to write about my neighborhood. Mayordomo was the first published result. With that, nonfiction became my preferred means to explore the ways of community, which is of course to say place, and therefore in my situation local economies and small-scale agriculture.

When looking for a copy of Some Instructions recently, I was amused to find the following comment made by an anonymous customer on amazon.com: “The nameless narrator of Stanley Crawford’s book has something in common with today’s survivalists of Ruby Ridge and the Republic of Texas.” It’s kind of an offbeat comment, but something about it struck me—do you think of that book, or any of your other fiction, as somehow responding to a particularly Western brand of rugged individualism?

- Not yet, at least. I have a draft of novel set in the early 1950s West (or the one I think you have in mind) which I have kept parked for a couple of years now but intend to get back to, and though it’s not satirical it still wouldn’t quite fit in that box.

The buzzword at the time of Some Instructions was “self-sufficiency.” Survivalism was probably out there, perhaps in its incipient stages, but not yet on my radar. And self-sufficiency, in its extreme form—grow your own food, make your own clothes, build your own shelter, acquire all the tools you need to do everything, etc., left out community in the large sense, just as did the early stages of the organic movement, though it did not attempt to severely seal itself off from the rest of the world in the way the survivalist movement tried to. Or for that matter the narrator of Some Instructions. Personally I was pulled in opposite directions. I wanted to be at least somewhat free of the complex industrial systems that seemed to be entering a phase of instability; and yet I could not entirely dismiss E.M. Forster’s dictum, “Only connect.” For some years I was attracted to various cooperative enterprises until I finally settled on the quasi-cooperative Santa Fe Farmers’ Market, for which I worked as a volunteer board chair for 14 years, and then a paid staff member for three years, and then again as a board member for a couple of more years, until about a month ago.

Are there any writers working in the American West that you see as having been particularly influential on your fiction?

- Would it sound ungrateful to say “no”? New Mexico is another country, and it faces south when not facing inward. I was raised in California, went to school there, which has other flavors of Westness than what I feel around us, up in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Idaho. I recently discovered Kent Haruf’s stunning Plainsong, but he’s perhaps a little too Great Plains to be considered Western, and sometimes Annie Proulx’s stories evoke in a startling way the Wyoming of a late brother-in-law. The part of the country I’m most fascinated with now is the Great Plains—I loved Ian Frazier’s book by that name—though I doubt I will ever write about it.

Funny that you mention “looking south,” because I wanted to ask you about Latin American writers: I was interested to learn that you see One Hundred Years of Solitude as having inspired you around the time you were writing Log. What Latin American writers, if any, are engaging you these days?

- Some years back I became an avid reader of Vargas Llosa’s more interesting fiction, Conversations in the Cathedral and City of Dogs (if I remember the titles correctly, and I believe the second one had two different titles in English), and particularly The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta. Mayta is stunning in its mid-sentence shifts in point of view, switching between the journalist in search of the “real” Mayta and the subjects he is interviewing; after the initial shock it comes to seem quite natural, logical even. Beyond Llosa, and certainly not his later potboilers, I haven’t read anything as engaging, though I have a sense there must be something out there. In this connection, I must mention a gem of a book, So Many Books: Reading and Publishing in an Age of Abundance, by the Mexican businessman Gabriel Zaid. " - Interview with Alex Young